The Star-Child

- 书名:

- 夜莺与玫瑰

- 作者:

- 王尔德

- 本章字数:

- 32050

- 更新时间:

- 2024-03-06 14:00:15

Once upon a time two poor Woodcutters were making their way home through a great pine-forest. It was winter, and a night of bitter cold. The snow lay thick upon the ground, and upon the branches of the trees; the frost kept snapping the little twigs on either side of them, as they passed; and when they came to the Mountain-Torrent she was hanging motionless in air, for the Ice-

King had kissed her.

So cold was it that even the animals and the birds did not know what to make of it.

“Ugh!” snarled the Wolf, as he limped through the brushwood with his tail between his legs, “this is perfectly monstrous weather.

Why doesn’t the Government look to it?”

“Weet! weet! weet!” twittered the green Linnets, “the old Earth is dead and they have laid her out in her white shroud.”

“The Earth is going to be married, and this is her bridal dress,” whispered the Turtle-doves to each other. Their little pink feet were quite frost-bitten, but they felt that it was their duty to take a romantic view of the situation.

“Nonsense!” growled the Wolf. “I tell you that it is all the fault of the Government, and if you don’t believe me I shall eat you.” The Wolf had a thoroughly practical mind, and was never at a loss for a good argument.

“Well, for my own part,” said the Woodpecker, who was a born philosopher, “I don’t care an atomic theory for explanations.

If a thing is so, it is so, and at present it is terribly cold.”

Terribly cold it certainly was. The little Squirrels, who lived inside the tall fir-tree, kept rubbing each other’s noses to keep themselves warm, and the Rabbits curled themselves up in their holes, and did not venture even to look out of doors. The only people who seemed to enjoy it were the great horned Owls. Their feathers were quite stiff with rime, but they did not mind, and they rolled their large yellow eyes, and called out to each other across the forest, “Tu-whit! Tu-whoo! Tu-whit! Tu-whoo! what delightful weather we are having!”

On and on went the two Woodcutters, blowing lustily upon their fingers, and stamping with their huge iron-shod boots upon the caked snow. Once they sank into a deep drift, and came out as white as millers are, when the stones are grinding;and once they slipped on the hard smooth ice where the marshwater was frozen, and their faggots fell out of their bundles,and they had to pick them up and bind them together again;and once they thought that they had lost their way, and a great terror seized on them, for they knew that the Snow is cruel to those who sleep in her arms. But they put their trust in the good Saint Martin, who watches over all travellers, and retraced their steps, and went warily, and at last they reached the outskirts of the forest, and saw, far down in the valley beneath them, the lights of the village in which they dwelt.

So overjoyed were they at their deliverance that they laughed aloud, and the Earth seemed to them like a flower of silver, and the Moon like a flower of gold.

Yet, after they had laughed they became sad, for they remembered their poverty, and one of them said to the other, “Why did we make merry, seeing that life is for the rich, and not for such as we are? Better that we had died of cold in the forest, or that some wild beast had fallen upon us and slain us.”

“Truly,” answered his companion, “much is given to some,and little is given to others. Injustice has parcelled out the world,nor is there equal division of aught save of sorrow.”

But as they were bewailing their misery to each other this strange thing happened. There fell from heaven a very bright and beautiful star. It slipped down the side of the sky, passing by the other stars in its course, and, as they watched it wondering, it seemed to them to sink behind a clump of willow-trees that stood hard by a little sheepfold no more than a stone’s-throw away.

“Why! there is a crock of gold for whoever finds it,” they cried, and they set to and ran, so eager were they for the gold.

And one of them ran faster than his mate, and outstripped him, and forced his way through the willows, and came out on the other side, and lo! there was indeed a thing of gold lying on the white snow. So he hastened towards it, and stooping down placed his hands upon it, and it was a cloak of golden tissue, curiously wrought with stars, and wrapped in many folds. And he cried out to his comrade that he had found the treasure that had fallen from the sky, and when his comrade had come up, they sat them down in the snow, and loosened the folds of the cloak that they might divide the pieces of gold. But, alas! no gold was in it, nor silver,nor, indeed, treasure of any kind, but only a little child who was asleep.

And one of them said to the other: “This is a bitter ending to our hope, nor have we any good fortune, for what doth a child profit a man? Let us leave it here, and go our way, seeing that we are poor men, and have children of our own whose bread we may not give to another.”

But his companion answered him: “Nay, but it were an evil thing to leave the child to perish here in the snow, and though I am as poor as thou art, and have many mouths to feed, and but little in the pot, yet will I bring it home with me, and my wife shall have care of it.”

So very tenderly he took up the child, and wrapped the cloak around it to shield it from the harsh cold, and made his way down the hill to the village, his comrade marvelling much at his foolishness and softness of heart.

And when they came to the village, his comrade said to him,“Thou hast the child, therefore give me the cloak, for it is meet that we should share.”

But he answered him: “Nay, for the cloak is neither mine nor thine, but the child’s only,” and he bade him Godspeed, and went to his own house and knocked.

And when his wife opened the door and saw that her husband had returned safe to her, she put her arms round his neck and kissed him, and took from his back the bundle of faggots, and brushed the snow off his boots, and bade him come in.

But he said to her, “I have found something in the forest, and I have brought it to thee to have care of it,” and he stirred not from the threshold.

“What is it?” she cried. “Show it to me, for the house is bare,and we have need of many things.” And he drew the cloak back,and showed her the sleeping child.

“Alack, goodman!” she murmured, “have we not children of our own, that thou must needs bring a changeling to sit by the hearth? And who knows if it will not bring us bad fortune? And how shall we tend it?” And she was wroth against him.

“Nay, but it is a Star-Child,” he answered; and he told her the strange manner of the finding of it.

But she would not be appeased, but mocked at him, and spoke angrily, and cried: “Our children lack bread, and shall we feed the child of another? Who is there who careth for us? And who giveth us food?”

“Nay, but God careth for the sparrows even, and feedeth them,” he answered.

“Do not the sparrows die of hunger in the winter?” she asked.

“And is it not winter now?”

And the man answered nothing, but stirred not from the threshold.

And a bitter wind from the forest came in through the open door, and made her tremble, and she shivered, and said to him:“Wilt thou not close the door? There cometh a bitter wind into the house, and I am cold.”

“Into a house where a heart is hard cometh there not always a bitter wind?” he asked. And the woman answered him nothing,but crept closer to the fire.

And after a time she turned round and looked at him, and her eyes were full of tears. And he came in swiftly, and placed the child in her arms, and she kissed it, and laid it in a little bed where the youngest of their own children was lying. And on the morrow the Woodcutter took the curious cloak of gold and placed it in a great chest, and a chain of amber that was round the child’s neck his wife took and set it in the chest also.

So the Star-Child was brought up with the children of the Woodcutter, and sat at the same board with them, and was their playmate. And every year he became more beautiful to look at,so that all those who dwelt in the village were filled with wonder,for, while they were swarthy and black-haired, he was white and delicate as sawn ivory, and his curls were like the rings of the daffodil. His lips, also, were like the petals of a red flower, and his eyes were like violets by a river of pure water, and his body like the narcissus of a field where the mower comes not.

Yet did his beauty work him evil. For he grew proud, and cruel, and selfish. The children of the Woodcutter, and the other children of the village, he despised, saying that they were of mean parentage, while he was noble, being sprang from a Star, and he made himself master over them, and called them his servants. No pity had he for the poor, or for those who were blind or maimed or in any way afflicted, but would cast stones at them and drive them forth on to the highway, and bid them beg their bread elsewhere,so that none save the outlaws came twice to that village to ask for alms. Indeed, he was as one enamoured of beauty, and would mock at the weakly and ill-favoured, and make jest of them; and himself he loved, and in summer, when the winds were still, he would lie by the well in the priest’s orchard and look down at the marvel of his own face, and laugh for the pleasure he had in his fairness.

Often did the Woodcutter and his wife chide him, and say:“We did not deal with thee as thou dealest with those who are left desolate, and have none to succour them. Wherefore art thou so cruel to all who need pity?”

Often did the old priest send for him, and seek to teach him the love of living things, saying to him: “The fly is thy brother. Do it no harm. The wild birds that roam through the forest have their freedom. Snare them not for thy pleasure.

God made the blind-worm and the mole, and each has its place.

Who art thou to bring pain into God’s world? Even the cattle of the field praise Him.”

But the Star-Child heeded not their words, but would frown and flout, and go back to his companions, and lead them. And his companions followed him, for he was fair, and fleet of foot, and could dance, and pipe, and make music. And wherever the Star-

Child led them they followed, and whatever the Star-Child bade them do, that did they. And when he pierced with a sharp reed the dim eyes of the mole, they laughed, and when he cast stones at the leper they laughed also. And in all things he ruled them, and they became hard of heart even as he was.

Now there passed one day through the village a poor beggarwoman.

Her garments were torn and ragged, and her feet were bleeding from the rough road on which she had travelled, and she was in very evil plight. And being weary she sat her down under a chestnut-tree to rest.

But when the Star-Child saw her, he said to his companions,“See! There sitteth a foul beggar-woman under that fair and greenleaved tree. Come, let us drive her hence, for she is ugly and illfavoured.”

So he came near and threw stones at her, and mocked her,and she looked at him with terror in her eyes, nor did she move her gaze from him. And when the Woodcutter, who was cleaving logs in a haggard hard by, saw what the Star-Child was doing, he ran up and rebuked him, and said to him: “Surely thou art hard of heart and knowest not mercy, for what evil has this poor woman done to thee that thou shouldst treat her in this wise?”

And the Star-Child grew red with anger, and stamped his foot upon the ground, and said, “Who art thou to question me what I do? I am no son of thine to do thy bidding.”

“Thou speakest truly,” answered the Woodcutter, “yet did I show thee pity when I found thee in the forest.”

And when the woman heard these words she gave a loud cry,and fell into a swoon. And the Woodcutter carried her to his own house, and his wife had care of her, and when she rose up from the swoon into which she had fallen, they set meat and drink before her, and bade her have comfort.

But she would neither eat nor drink, but said to the Woodcutter, “Didst thou not say that the child was found in the forest? And was it not ten years from this day?”

And the Woodcutter answered, “Yea, it was in the forest that I found him, and it is ten years from this day.”

“And what signs didst thou find with him?” she cried. “Bare he not upon his neck a chain of amber? Was not round him a cloak of gold tissue broidered with stars?”

“Truly,” answered the Woodcutter, “it was even as thou sayest.” And he took the cloak and the amber chain from the chest where they lay, and showed them to her.

And when she saw them she wept for joy, and said, “He is my little son whom I lost in the forest. I pray thee send for him quickly, for in search of him have I wandered over the whole world.”

So the Woodcutter and his wife went out and called to the Star-Child, and said to him, “Go into the house, and there shalt thou find thy mother, who is waiting for thee.”

So he ran in, filled with wonder and great gladness. But when he saw her who was waiting there, he laughed scornfully and said, “Why, where is my mother? For I see none here but this vile beggar-woman.”

And the woman answered him, “I am thy mother.”

“Thou art mad to say so,” cried the Star-Child angrily. “I am no son of thine, for thou art a beggar, and ugly, and in rags.

Therefore get thee hence, and let me see thy foul face no more.”

“Nay, but thou art indeed my little son, whom I bore in the forest,” she cried, and she fell on her knees, and held out her arms to him. “The robbers stole thee from me, and left thee to die,” she murmured, “but I recognised thee when I saw thee, and the signs also have I recognised, the cloak of golden tissue and the amber chain. Therefore I pray thee come with me, for over the whole world have I wandered in search of thee. Come with me, my son,for I have need of thy love.”

But the Star-Child stirred not from his place, but shut the doors of his heart against her, nor was there any sound heard save the sound of the woman weeping for pain.

And at last he spoke to her, and his voice was hard and bitter. “If in very truth thou art my mother,” he said, “it had been better hadst thou stayed away, and not come here to bring me to shame, seeing that I thought I was the child of some Star, and not a beggar’s child, as thou tellest me that I am. Therefore get thee hence, and let me see thee no more.”

“Alas! my son,” she cried, “wilt thou not kiss me before I go?

For I have suffered much to find thee.”

“Nay,” said the Star-Child, “but thou art too foul to look at,and rather would I kiss the adder or the toad than thee.”

So the woman rose up, and went away into the forest weeping bitterly, and when the Star-Child saw that she had gone,he was glad, and ran back to his playmates that he might play with them.

But when they beheld him coming, they mocked him and said, “Why, thou art as foul as the toad, and as loathsome as the adder. Get thee hence, for we will not suffer thee to play with us,”

and they drove him out of the garden.

And the Star-Child frowned and said to himself, “What is this that they say to me? I will go to the well of water and look into it,and it shall tell me of my beauty.”

So he went to the well of water and looked into it, and lo!

his face was as the face of a toad, and his body was scaled like an adder. And he flung himself down on the grass and wept, and said to himself, “Surely this has come upon me by reason of my sin. For I have denied my mother, and driven her away, and been proud, and cruel to her. Wherefore I will go and seek her through the whole world, nor will I rest till I have found her.”

And there came to him the little daughter of the Woodcutter,and she put her hand upon his shoulder and said, “What doth it matter if thou hast lost thy comeliness? Stay with us, and I will not mock at thee.”

And he said to her, “Nay, but I have been cruel to my mother,and as a punishment has this evil been sent to me. Wherefore I must go hence, and wander through the world till I find her, and she give me her forgiveness.”

So he ran away into the forest and called out to his mother to come to him, but there was no answer. All day long he called to her, and, when the sun set he lay down to sleep on a bed of leaves,and the birds and the animals fled from him, for they remembered his cruelty, and he was alone save for the toad that watched him,and the slow adder that crawled past.

And in the morning he rose up, and plucked some bitter berries from the trees and ate them, and took his way through the great wood, weeping sorely. And of everything that he met he made inquiry if perchance they had seen his mother.

He said to the Mole, “Thou canst go beneath the earth. Tell me, is my mother there?”

And the Mole answered, “Thou hast blinded mine eyes. How should I know?”

He said to the Linnet, “Thou canst fly over the tops of the tall trees, and canst see the whole world. Tell me, canst thou see my mother?”

And the Linnet answered, “Thou hast clipt my wings for thy pleasure. How should I fly?”

And to the little Squirrel who lived in the fir-tree, and was lonely, he said,“Where is my mother?”

And the Squirrel answered, “Thou hast slain mine. Dost thou seek to slay thine also?”

And the Star-Child wept and bowed his head, and prayed forgiveness of God’s things, and went on through the forest,seeking for the beggar-woman. And on the third day he came to the other side of the forest and went down into the plain.

And when he passed through the villages the children mocked him, and threw stones at him, and the carlots would not suffer him even to sleep in the byres lest he might bring mildew on the stored corn, so foul was he to look at, and their hired men drove him away, and there was none who had pity on him. Nor could he hear anywhere of the beggar-woman who was his mother, though for the space of three years he wandered over the world, and often seemed to see her on the road in front of him, and would call to her, and run after her till the sharp flints made his feet to bleed.

But overtake her he could not, and those who dwelt by the way did ever deny that they had seen her, or any like to her, and they made sport of his sorrow.

For the space of three years he wandered over the world, and in the world there was neither love nor loving-kindness nor charity for him, but it was even such a world as he had made for himself in the days of his great pride.

And one evening he came to the gate of a strong-walled city that stood by a river, and, weary and footsore though he was, he made to enter in. But the soldiers who stood on guard dropped their halberts across the entrance, and said roughly to him, “What is thy business in the city?”

“I am seeking for my mother,” he answered, “and I pray ye to suffer me to pass, for it may be that she is in this city.”

But they mocked at him, and one of them wagged a black beard, and set down his shield and cried, “Of a truth, thy mother will not be merry when she sees thee, for thou art more illfavoured than the toad of the marsh, or the adder that crawls in the fen. Get thee gone. Get thee gone. Thy mother dwells not in this city.”

And another, who held a yellow banner in his hand, said to him, “Who is thy mother, and wherefore art thou seeking for her?”

And he answered, “My mother is a beggar even as I am, and I have treated her evilly, and I pray ye to suffer me to pass that she may give me her forgiveness, if it be that she tarrieth in this city.”

But they would not, and pricked him with their spears.

And, as he turned away weeping, one whose armour was inlaid with gilt flowers, and on whose helmet couched a lion that had wings, came up and made inquiry of the soldiers who it was who had sought entrance. And they said to him, “It is a beggar and the child of a beggar, and we have driven him away.”

“Nay,” he cried, laughing, “but we will sell the foul thing for a slave, and his price shall be the price of a bowl of sweet wine.”

And an old and evil-visaged man who was passing by called out, and said, “I will buy him for that price,” and, when he had paid the price, he took the Star-Child by the hand and led him into the city.

And after that they had gone through many streets they came to a little door that was set in a wall that was covered with a pomegranate tree. And the old man touched the door with a ring of graved jasper and it opened, and they went down five steps of brass into a garden filled with black poppies and green jars of burnt clay. And the old man took then from his turban a scarf of figured silk, and bound with it the eyes of the Star-Child, and drave him in front of him. And when the scarf was taken off his eyes, the Star-Child found himself in a dungeon, that was lit by a lantern of horn.

And the old man set before him some mouldy bread on a trencher and said, “Eat,” and some brackish water in a cup and said, “Drink,” and when he had eaten and drunk, the old man went out, locking the door behind him and fastening it with an iron chain.

And on the morrow the old man, who was indeed the subtlest of the magicians of Libya and had learned his art from one who dwelt in the tombs of the Nile, came in to him and frowned at him, and said, “In a wood that is nigh to the gate of this city of Giaours there are three pieces of gold. One is of white gold, and another is of yellow gold, and the gold of the third one is red. Today thou shalt bring me the piece of white gold, and if thou bringest it not back, I will beat thee with a hundred stripes. Get thee away quickly, and at sunset I will be waiting for thee at the door of the garden. See that thou bringest the white gold, or it shall go ill with thee, for thou art my slave, and I have bought thee for the price of a bowl of sweet wine.” And he bound the eyes of the Star-Child with the scarf of figured silk, and led him through the house, and through the garden of poppies, and up the five steps of brass.

And having opened the little door with his ring he set him in the street.

And the Star-Child went out of the gate of the city, and came to the wood of which the Magician had spoken to him.

Now this wood was very fair to look at from without, and seemed full of singing birds and of sweet-scented flowers, and the Star-Child entered it gladly. Yet did its beauty profit him little, for wherever he went harsh briars and thorns shot up from the ground and encompassed him, and evil nettles stung him, and the thistle pierced him with her daggers, so that he was in sore distress.

Nor could he anywhere find the piece of white gold of which the Magician had spoken, though he sought for it from morn to noon,and from noon to sunset. And at sunset he set his face towards home, weeping bitterly, for he knew what fate was in store for him.

But when he had reached the outskirts of the wood, he heard from a thicket a cry as of some one in pain. And forgetting his own sorrow he ran back to the place, and saw there a little Hare caught in a trap that some hunter had set for it.

And the Star-Child had pity on it, and released it, and said to it, “I am myself but a slave, yet may I give thee thy freedom.”

And the Hare answered him, and said: “Surely thou hast given me freedom, and what shall I give thee in return?”

And the Star-Child said to it, “I am seeking for a piece of white gold, nor can I anywhere find it, and if I bring it not to my master he will beat me.”

“Come thou with me,” said the Hare, “and I will lead thee to it, for I know where it is hidden, and for what purpose.”

So the Star-Child went with the Hare, and lo! in the cleft of a great oak-tree he saw the piece of white gold that he was seeking.

And he was filled with joy, and seized it, and said to the Hare,“The service that I did to thee thou hast rendered back again many times over, and the kindness that I showed thee thou hast repaid a hundred-fold.”

“Nay,” answered the Hare, “but as thou dealt with me, so I did deal with thee,” and it ran away swiftly, and the Star-Child went towards the city.

Now at the gate of the city there was seated one who was a leper. Over his face hung a cowl of grey linen, and through the eyelets his eyes gleamed like red coals. And when he saw the Star-

Child coming, he struck upon a wooden bowl, and clattered his bell, and called out to him, and said, “Give me a piece of money,or I must die of hunger. For they have thrust me out of the city,and there is no one who has pity on me.”

“Alas!” cried the Star-Child, “I have but one piece of money in my wallet, and if I bring it not to my master he will beat me, for I am his slave.”

But the leper entreated him, and prayed of him, till the Star-

Child had pity, and gave him the piece of white gold.

And when he came to the Magician’s house, the Magician opened to him, and brought him in, and said to him, “Hast thou the piece of white gold?” And the Star-Child answered, “I have it not.” So the Magician fell upon him, and beat him, and set before him an empty trencher, and said, “Eat,” and an empty cup, and said, “Drink,” and flung him again into the dungeon.

And on the morrow the Magician came to him, and said, “If today thou bringest me not the piece of yellow gold, I will surely keep thee as my slave, and give thee three hundred stripes.”

So the Star-Child went to the wood, and all day long he searched for the piece of yellow gold, but nowhere could he find it. And at sunset he sat him down and began to weep, and as he was weeping there came to him the little Hare that he had rescued from the trap, and the Hare said to him, “Why art thou weeping?

And what dost thou seek in the wood?”

And the Star-Child answered, “I am seeking for a piece of yellow gold that is hidden here, and if I find it not my master will beat me, and keep me as a slave.”

“Follow me,” cried the Hare, and it ran through the wood till it came to a pool of water. And at the bottom of the pool the piece of yellow gold was lying.

“How shall I thank thee?” said the Star-Child, “for lo! this is the second time that you have succoured me.”

“Nay, but thou hadst pity on me first,” said the Hare, and it ran away swiftly.

And the Star-Child took the piece of yellow gold, and put it in his wallet, and hurried to the city. But the leper saw him coming, and ran to meet him, and knelt down and cried, “Give me a piece of money or I shall die of hunger.”

And the Star-Child said to him, “I have in my wallet but one piece of yellow gold, and if I bring it not to my master he will beat me and keep me as his slave.”

But the leper entreated him sore, so that the Star-Child had pity on him, and gave him the piece of yellow gold.

And when he came to the Magician’s house, the Magician opened to him, and brought him in, and said to him, “Hast thou the piece of yellow gold?” And the Star-Child said to him, “I have not.” So the Magician fell upon him, and beat him, and loaded him with chains, and cast him again into the dungeon.

And on the morrow the Magician came to him, and said, “If today thou bringest me the piece of red gold I will set thee free,but if thou bringest it not I will surely slay thee.”

So the Star-Child went to the wood, and all day long he searched for the piece of red gold, but nowhere could he find it.

And at evening he sat him down and wept, and as he was weeping there came to him the little Hare.

And the Hare said to him, “The piece of red gold that thou seekest is in the cavern that is behind thee. Therefore weep no more but be glad.”

“How shall I reward thee?” cried the Star-Child, “for lo! this is the third time thou hast succoured me.”

“Nay, but thou hadst pity on me first,” said the Hare, and it ran away swiftly.

And the Star-Child entered the cavern, and in its farthest corner he found the piece of red gold. So he put it in his wallet,and hurried to the city. And the leper seeing him coming, stood in the centre of the road, and cried out, and said to him, “Give me the piece of red money, or I must die,” and the Star-Child had pity on him again, and gave him the piece of red gold, saying, “Thy need is greater than mine.” Yet was his heart heavy, for he knew what evil fate awaited him.

But lo! as he passed through the gate of the city, the guards bowed down and made obeisance to him, saying, “How beautiful is our lord!” and a crowd of citizens followed him, and cried out,“Surely there is none so beautiful in the whole world!” so that the Star-Child wept, and said to himself, “They are mocking me, and making light of my misery.” And so large was the concourse of the people, that he lost the threads of his way, and found himself at last in a great square, in which there was a palace of a King.

And the gate of the palace opened, and the priests and the high officers of the city ran forth to meet him, and they abased themselves before him, and said, “Thou art our lord for whom we have been waiting, and the son of our King.”

And the Star-Child answered them and said, “I am no king’s son, but the child of a poor beggar-woman. And how say ye that I am beautiful, for I know that I am evil to look at?”

Then he, whose armour was inlaid with gilt flowers, and on whose helmet crouched a lion that had wings, held up a shield,and cried, “How saith my lord that he is not beautiful?”

And the Star-Child looked, and lo! his face was even as it had been, and his comeliness had come back to him, and he saw that in his eyes which he had not seen there before.

And the priests and the high officers knelt down and said to him, “It was prophesied of old that on this day should come he who was to rule over us. Therefore, let our lord take this crown and this sceptre, and be in his justice and mercy our King over us.”

But he said to them, “I am not worthy, for I have denied the mother who bore me, nor may I rest till I have found her, and known her forgiveness. Therefore, let me go, for I must wander again over the world, and may not tarry here, though ye bring me the crown and the sceptre.” And as he spake he turned his face from them towards the street that led to the gate of the city, and lo! amongst the crowd that pressed round the soldiers, he saw the beggar-woman who was his mother, and at her side stood the leper, who had sat by the road.

And a cry of joy broke from his lips, and he ran over, and kneeling down he kissed the wounds on his mother’s feet, and wet them with his tears. He bowed his head in the dust, and sobbing, as one whose heart might break, he said to her: “Mother,I denied thee in the hour of my pride. Accept me in the hour of my humility. Mother, I gave thee hatred. Do thou give me love.

Mother, I rejected thee. Receive thy child now.” But the beggarwoman answered him not a word.

And he reached out his hands, and clasped the white feet of the leper, and said to him: “Thrice did I give thee of my mercy.

Bid my mother speak to me once.” But the leper answered him not a word.

And he sobbed again and said: “Mother, my suffering is greater than I can bear. Give me thy forgiveness, and let me go back to the forest.” And the beggar-woman put her hand on his head, and said to him, “Rise,” and the leper put his hand on his head, and said to him, “Rise,” also.

And he rose up from his feet, and looked at them, and lo!

they were a King and a Queen.

And the Queen said to him, “This is thy father whom thou hast succoured.”

And the King said, “This is thy mother whose feet thou hast washed with thy tears.” And they fell on his neck and kissed him,and brought him into the palace and clothed him in fair raiment,and set the crown upon his head, and the sceptre in his hand, and over the city that stood by the river he ruled, and was its lord.

Much justice and mercy did he show to all, and the evil Magician he banished, and to the Woodcutter and his wife he sent many rich gifts, and to their children he gave high honour. Nor would he suffer any to be cruel to bird or beast, but taught love and lovingkindness and charity, and to the poor he gave bread, and to the naked he gave raiment, and there was peace and plenty in the land.

Yet ruled he not long, so great had been his suffering, and so bitter the fire of his testing, that after the space of three years he died. And he who came after him ruled evilly.

已经读完最后一章啦!

90%的人强烈推荐

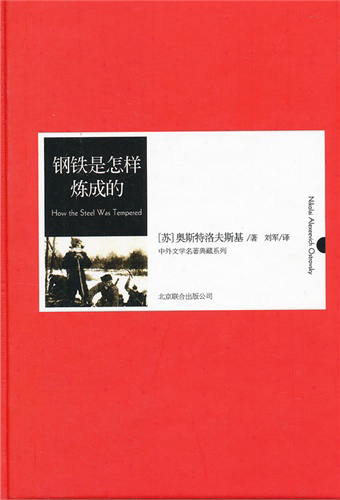

钢铁是怎样炼成的(中外文学名典藏系列)

第 一 部 一

- 书名:

- 钢铁是怎样炼成的(中外文学名典藏系列)

- 作者:

- [苏]奥斯特洛夫斯基

- 本章字数:

- 12190

“节前补考的,都给我站起来!”

身穿法衣的胖子正恶狠狠地瞪着全班的学生。他就是沃希利神父,脖子上挂着一个沉甸甸的十字架。

站起来的六个孩子——四个男生、两个女生——惶恐不安,“你俩坐下。”神父向那两个女孩边说边挥了挥手。

她俩立即坐下,但是依然丝毫不敢放松。

沃希利神父那双恶狠狠的小眼睛便转到四个男孩身上。

“小混蛋们,到这儿来!”

神父说着站起身来,移开了椅子,闯到这挤成一团的四个男生面前。

“你们这些小混蛋!谁抽烟?”

四个孩子怯声作答:“神父!我们……我们都不会抽烟。”

神父听了气得咬牙切齿。

“混账东西,都不抽烟,哼!真是见鬼!那面团里的烟味儿是从哪儿来的?谁都不抽烟吗?好!咱们这就来看看!把口袋都给我翻过来!快点!听见没有?翻过来!”

其中有三个孩子动手把口袋里的东西掏了出来,放在桌上。

神父仔仔细细地查看他们口袋里面的每一条缝隙,想找出一点烟末儿,可是他什么也没有发现。于是,就转身朝向了第四个男孩——这个孩子长着一双黑眼睛,穿着破旧的灰色衬衫和膝盖处打着补丁的蓝色裤子。

“你为什么像木头似的立在那里不动?”

黑眼睛的小孩恨透了神父,他盯着神父,小声地说道:“我一个口袋也没有。”他一边说一边伸手摸了摸那缝起来的衣袋口。

“哼!一个口袋也没有?你认为这样我就不清楚是谁把复活节的面团给糟蹋了吗?你认为现在学校还会要你吗?哼!你这捣蛋鬼,这次绝不能便宜你了。上次多亏你母亲那么恳求才没有把你开除,这次无论如何也不行了。你给我滚出去!”他用力揪住那小孩的一只耳朵,将他拖到走廊里,随手就关上了门。

整个教室里没有一丝声响,同学们都吓得缩着脖子。谁也不清楚保尔·柯察金为什么被开除,只有保尔的好朋友谢廖沙?布洛扎克心知肚明——他们六个功课不及格的学生在神父家厨房里等着补考的时候,他亲眼目睹了保尔将一撮烟末儿撒在准备做复活节蒸糕的面团上。

被开除的保尔坐在学校门口底下的一层台阶上。他现在只想着一个问题——该怎么回家。他该怎么向在税务官家里当厨娘、每天从早忙到晚、对什么事都非常认真的母亲解释这件事情呢?

想到这儿,他不禁急出了泪水,心里盘算着:“我现在该怎么办呢?都怪这个该死的神父。我为什么要在他的面团上撒上一把烟末儿呢?那本来是辛辽沙指使我干的。他说:‘来,我们给这讨厌的恶鬼撒一把烟末。’我们就撒上去了。可现在辛辽沙倒逃脱了,我呢,十有八九得被开除了。”

其实,保尔和沃希利神父早就结下了仇。曾有一天,保尔与米什卡·列夫丘科夫打架,神父不让他回家吃午饭。为了避免他独自一人在教室里淘气,就让他和高年级的学生在一起,坐在教室后面的凳子上。

那个高年级的教师很瘦,穿了件黑色上衣,正在给学生讲解地球和天体。保尔听着,惊奇万分地张大了嘴巴。什么地球已经存在了好几百万年了,什么星星也跟地球相像等等。他听后觉得很奇怪,几乎想立刻站起来问:“先生,这跟圣经上说的完全两样呀。”但是,他没敢问,因为他怕被赶出教室。

保尔的圣经课,神父总是给他五分。祈祷词以及《新约》、《旧约》,甚至上帝哪一天创造了哪一种东西,他都背得滚瓜烂熟。所以,关于地球这件事情,保尔决心问问沃希利神父。等到下次上圣经课的时候,神父刚坐下,保尔就举起手来,在得到神父的允许后,他立刻起身问道:“神父,为什么高年级的老师说地球已经存在了好几百万年了,根本不像《圣经》上说的那样只存在五千年……”他突然被沃希利神父那尖厉的喊叫声给打断了:“混账东西,胡说八道!你就是这样学《圣经》的吗?”

保尔根本没来得及回答,神父就已揪住了他的两只耳朵,并将他的头往墙上撞。一分钟之后,被撞得鼻青脸肿、吓得魂不附体的保尔被推到了走廊里。

保尔回到家后,他的母亲又严厉地责备了他一番。

第二天,他母亲来到学校,恳请沃希利神父让她的孩子回校上课。就是从这天起,保尔就恨透了神父,但是既恨他,又怕他。保尔决不会饶恕欺负过他的人,即便是稍加侮辱,他也不能善罢甘休,当然,他不会轻易忘记被神父冤枉的这一顿毒打,但他只是怀恨于心,从不表露出来。

他还受过沃希利神父的很多次歧视凌辱:往往为了一些鸡毛蒜皮的小事,神父就把他赶出教室,还有接连好几个星期都罚他站在角落里,而且从来不过问他的功课,由此造成他不得不在复活节前同那几个功课不及格的同学一起到神父家里去补考。他们在厨房里等候的时候,保尔就将一撮烟末撒在复活节蒸糕用的面团上。

这件事虽然除了辛辽沙外无人目睹,但是神父还是猜到了是谁干的。

下课了,孩子们蜂拥而出,来到院子里,围住了保尔。忧心忡忡的保尔静静地坐在那儿,一句话也不想说。辛辽沙躲在教室里没有出来,他深悔自己的过错,却不知道如何帮助保尔。

校长叶弗列姆?沃希利耶维奇从办公室的窗口探出头来,他那低沉的声音,使保尔大吃一惊。校长喊道:“让柯察金马上到我这里来!”

保尔的心怦怦直跳,朝办公室走去。

车站饭馆的老板是一个面色苍白、眼睛无神并且上了年纪的人,他向站在一旁的保尔瞥了一眼,并问道: “他几岁了?”

“十二了。”保尔的母亲回答。

“可以,让他留下吧。条件是这样:工钱每月八卢布,上班的时候管饭,上班干一天一夜,在家休息一天一夜——但不准偷东西。”

“不会的,老板,不会的!我敢保证保尔什么也不偷。”保尔的母亲连忙回答。

“好,那让他今天就上班。”老板命令道,然后又转过身去,向旁边那个站在柜台后面的女招待说:“契那,带这个孩子到洗刷间去,转告弗朗茜,让他代替格里什加。”

女招待正在切火腿,她放下了刀子,向保尔点了点头,穿过店堂,向那扇通往洗刷间的旁门走去。保尔跟在女招待的身后,他的母亲也紧随其后,小声对他说:“保尔,亲爱的,你干活要卖力气,可别丢脸啊。”

她以忧郁的目光看着儿子进去之后,才朝门口走去。

洗刷间里的活儿特别紧张,桌子上堆着一大堆盘碟和刀叉,几个妇女正用搭在肩膀上的毛巾擦着这些餐具。

一个年纪比保尔稍大、长着一头蓬乱的棕红色头发的男孩,正在两个大茶炉前忙得不可开交。

洗餐具的大锅里,开水翻滚着蒸气,把整个洗刷间弄得热气腾腾。刚一进来,保尔看不清女工们的脸,他站在那里,不知所措。

契那走到一个正洗盘子的女人身旁,将手搭在她的肩膀上说:“弗朗茜,看,这是给你们雇来的小伙计,代替格里什加的。你告诉他该干些什么。”

契那转过身来指着那个叫弗朗茜的女人,对保尔说:“她是这里的领班。她叫你做什么,你就做什么。”说完后便转身朝店堂走去。

“是。”保尔轻声回答,同时看着站在他前面的弗朗茜,等候她的安排。弗朗茜擦了擦额头上的汗珠,从上到下打量了保尔一番,好似在估量他能否称职。她卷起那只从胳膊上松散下来的袖子,用一种极其深沉而又动听的声音说:“小家伙,你的活儿很简单:每天早晨要按时把这个大锅里的水烧开,并让锅里一直有开水。当然,木柴是你自己劈,还有那两个大茶炉也是你的活儿。另外呢,人手不够时,你就帮着擦刀叉,把脏水提出去倒掉。亲爱的,你的活儿不少,够你忙的了。”她说的是科斯特罗马地方的方言,总把重音放在字母“a”上。她说话的这种口音和那张长着翘鼻子、泛着红晕的脸庞,让保尔心中感到了一些愉快。

“看来,这位大婶挺和气的。”保尔心里这样想,于是就鼓起勇气问弗朗茜:“那我现在做什么呢,大婶?”

保尔的话音刚落,洗刷间的女工们便哄然大笑起来,将他的话语给淹没了。

“哈哈哈……弗朗茜认了一个侄子……”

“哈哈……”弗朗茜本人笑得最厉害。

水蒸气弥漫着整个洗刷间,这让保尔看不清弗朗茜的脸庞,其实她才十八岁。

保尔觉得很尴尬,于是他转过身问一个男孩: “现在我该做什么呢?”

那个男孩子调皮地回答:

“还是问你的大婶吧,她会详细地告诉你的,我只是这里的临时工。”说完,他转身就朝厨房跑去。

这时,保尔听到一个年纪稍大的洗餐具的女工说:“到这里来,帮我擦叉子吧。你们怎么笑得那么开心呢?这孩子到底说了什么好笑的话?”她递给保尔一条毛巾,说道:“给你,拿着,一头用牙咬住,一头用手拉紧,然后把叉齿在上面来回地擦,要擦得干干净净,一点儿脏东西也不许有。我们这里对这件事很认真。老爷们都仔细地查看叉子,如果他们发现一丝脏东西,那就糟糕了,老板娘就会马上把你赶走。”

“什么?老板娘?”保尔糊涂了,“刚才雇我那个人不是老板吗?”

那女工笑了起来:

“孩子,你不知道,我们的老板只是个摆设,是个废物,这里的事情都由老板娘做主。她今天不在这里。你干几天就清楚了。”

洗刷间的门开了,三个堂倌走了进来,每个人都抱着一大摞脏盘子。

其中那个宽肩膀、斜眼睛、四方大脸的家伙说道:“要快点干啊。十二点的班车马上就到了,可你们还是这么磨磨蹭蹭的。”

他看见了保尔,便问道:

“这是谁?”

“新来的。”弗朗茜回答道。

“哦,新来的,”他说,“那你可要当心,”他边说边把一只大手按到保尔的肩膀上,把保尔推到那两个大茶炉前面,“这两个大茶炉你时刻都得准备好,但是,你瞧瞧,现在这一个火已灭了,这一个也奄奄一息了。今天先饶了你,明天再这样,你就得挨耳光。听明白了吗?”

保尔没有说什么,就动手烧茶炉了。

保尔的劳动生涯就这样开始了。他从来没有像第一天工作那样卖力气。他很清楚:在这里不能像在家里那样,在家可以不听母亲的话;但是在这里,要是不听话,就得挨耳光——那个斜眼的堂倌说得很明白。

保尔用脱下来的一只靴子盖住炉筒,朝那两个大茶炉的炭火使劲鼓风,于是,那两个能盛四桶水的大肚子茶炉就冒出了火星。接着,他又把一桶脏水提走,倒在污水池里,把湿木柴堆到大锅旁边,又把湿抹布放在烧开了水的茶炉上烘干。总而言之,让他做什么,他就做什么。直到深夜,保尔才走到下面厨房里去,这时候他已经疲惫不堪了。那个年纪较大的洗餐具的女工阿尼西娅,望着他随手带上的门感慨道:“看这孩子,感觉真有点怪,他忙起来像个疯子似的。肯定是迫不得已才来这儿干活的。”

“是啊,这小伙子真不错,”弗朗茜说,“这样的人干起活来根本不用别人催。”

“干熟了就会偷懒了,”兰萨反驳道,“刚开始谁都会这么卖力……”

直到第二天早上七点,昼夜不停的保尔已经筋疲力尽了,他把两个烧开了的茶炉交给了替班的——这是个眼神凶恶的圆脸蛋男孩。

这个男孩看到保尔应该做的活儿都做了,两个茶炉里的水也都烧开了,于是他就将两只手插进口袋里,从紧紧咬住的牙缝里啐出一口唾沫,并用一副傲慢、蔑视的神态瞟了一眼保尔,然后用命令般的语气说道:“喂,小鬼!记住,明天早上六点来接班。”

“为什么六点?”保尔说,“换班时间是七点。”

“谁想七点换班,就让他七点换好了,可你六点就得来。要是再说废话,我就打肿你的狗脸作纪念。你这小子,刚来就摆臭架子!”

那些刚交班的洗餐具的女工们满怀兴趣地听着这两个孩子的对话。那个孩子盛气凌人的话语和挑衅的态度激怒了保尔。保尔向这个接班的孩子逼近了一步,真想狠狠地揍他一顿,可又怕第一天工作就被开除,所以才控制住自己没有动手。他气得满脸发紫,并对那个说男孩说道:“火气别太大,放客气点,别吓唬人,否则,够你受的!明早我七点来!如果你想打架,我奉陪。如果你想试一试,那就来吧!”

对方朝着大锅退了一步,出乎意料地瞅着怒气冲冲的保尔,他根本没想到自己会碰到这么强硬的钉子,于是有点措手不及。

“那好吧,咱们走着瞧!”他支吾着给自己找了个台阶下。

第一天就这样平安无事地过去了。当保尔昂首挺胸地回到家里的时候,他感到前所未有的心安理得,因为他是通过诚实的劳动挣得了休息的时间。他现在也是个劳动力了,谁也不能再说他是个寄生虫了。

清晨的太阳正从高高的锯木厂后面懒洋洋地升起来。保尔的那间小屋很快就进入了他的眼帘,瞧,马上就到了,就在列辛斯基庄园的后面。

“母亲肯定刚起床,可是我已经下班了。”他心里想着,便不由得加快了脚步,嘴里吹起了口哨。“被学校开除,但结果也不错。在学校里,那个该死的神父是绝对不会让我好好念书的。现在,我真恨不得吐他一脸唾沫!”保尔想着,不知不觉就到了家门口。在他推开小门的那一刻,他又下了个决心:“我一定要揍那个黄毛小子的狗脸,对,一定要揍他一顿。”

母亲正在院子里忙着烧茶炊。一看见保尔回来,她便慌慌地问道: “怎么样?”

“很好。”保尔回答。

母亲好像有什么话要告诉保尔。可是没等她开口,保尔就已经明白了。他从敞开的窗户望进去,看见了哥哥阿尔吉莫那宽大的后背。

“怎么,阿尔吉莫回来了?”他忐忑不安地问道。

“是的,昨天晚上回来的,以后他就住在家里了。他要调到调车场干活。”

保尔犹豫地推开了房门,走进屋里。

那个身材高大、背对着保尔坐在桌旁的人,回过头来,从浓密的、黑黑的眉毛下面直射出两股严厉的目光,盯着保尔,这是哥哥特有的目光。

“噢,撒烟末儿的孩子回来了?好,好,你干的好事,真了不起!”

保尔心知肚明,清楚与这位突然回家的哥哥谈话决不会有什么好结果。

“他什么都知道了,”保尔盘算着,“这回阿尔吉莫肯定会骂我、打我。”

保尔有点怕阿尔吉莫。

然而,阿尔吉莫并没有打算揍他弟弟。他坐在凳子上,两肘支着桌子,用一种不知是嘲弄还是轻蔑的目光盯着保尔。

“由此可见,你已经大学毕业,各门学科都学过了,现在满腹学问,却干起洗餐具的活儿来,是不是?”阿尔吉莫问。

保尔死盯着地板上那块破烂的地方,聚精会神地打量那个突出的钉子。但是,阿尔吉莫却从桌后站起身来,进了厨房。

“看样子不会挨打了。”保尔松了口气。

在喝茶的时候,阿尔吉莫心平气和地让保尔说说课堂上发生的事情。

保尔便如实地说出了事情的经过。

“现在你就这样胡闹,以后怎么办啊?”母亲发愁地说,“唉,我们可拿他怎么办呢?他这副德行究竟随了谁呢?上帝啊,为了这孩子,我操碎了心!”她抱怨着。

阿尔吉莫移开喝干的茶杯,对保尔郑重地说:“听见了吧,弟弟。过去的事就让它过去吧,以后你要小心些,干活儿别耍花招,该干的,都要干。如果这个地方又把你赶出来,那我就要狠狠地揍你,你要牢牢地记住,别再让咱母亲操心了。你这个捣蛋鬼,走到哪儿就闹到哪儿,到处闯祸。现在该闹够了吧。等你做满一年,我一定想办法把你调到调车场当学徒,一辈子给人家洗餐具有什么出息,应该学一门手艺。现在你还小,再过一年,我一定为你求情,说不定调车场会留下你。我已经调到这儿来了,以后就在这里干活,不用再让母亲替人家做工挣钱了。她在各种各样的畜生面前弯腰已经弯够了。可是你,保尔,你要争气,以后要做个有出息的人!”

说着他站了起来,挺直了那高大的身躯,顺手穿上了搭在椅背上的上衣,突然对母亲匆忙说了一声:“我有事要办,出去一个小时。”他边说边弯腰过了门楣,走了出去。当他到了院子里,经过窗户时,他又说道:“我给你带来了一双靴子和一把小刀,等会儿妈会拿给你。”

车站饭馆一天二十四小时营业。

这里是交通枢纽,有五条铁路线在此交轨。车站里总是挤满了人,只有在夜里两班车间隔的时候,才可以清静两三个小时。在这个车站上,成百上千列军用火车驶进车站,又从这里驶向四面八方,通常由前线开过来,向前线驶过去;无数的断肢伤残士兵从前线运来,而一批批一律身穿灰色军大衣的新兵又像洪流似的被不断地向前线运送。

保尔在饭馆里辛苦地工作了两年。这两年来,他所看到的只是厨房和洗刷间。在那个地下的大厨房里,工作极其紧张。那里有二十几个人在干活。十个堂倌穿梭般地从餐厅到厨房来回走动着、忙碌着。

在这两年里,保尔的工钱由八个卢布增长到十个卢布,人也变得又高又壮了。在这期间,他历尽磨难:最初在厨房里给厨子当下手,让煤烟熏了六个月,然后又被调到洗刷间,因为那个权力极大的厨子头儿不喜欢这个桀骜不驯的孩子,他担心保尔为了报复他的耳光而捅他一刀。当然,若不是保尔干活很卖力气,他们早就把他撵走了。保尔干的活比谁都多,好像他从来不知道疲倦。

当饭馆的生意很红火的时候,他就像疯子一样,一会儿端着盘子一步跨四五级楼梯,从餐厅跑到下面的厨房,一会儿又从厨房跑到餐厅。

深夜,每当饭馆的两个餐厅不再忙的时候,堂倌们就聚在下面厨房的仓库里,开始“幺”呀“九”呀地大赌起来。不只一次,保尔看见赌台上摊着很多钞票。看到这么多的钱,他一点也不吃惊,因为他清楚,客人们每次给他们半卢布或一卢布是常有的事,这些钱是他们积攒起来的。其实,他们中间无论是谁,只要当了一班就可以捞进三四十个卢布的小费。有了钱,他们便大吃大喝,连喝带赌。保尔特别憎恨他们。

“这些该死的混蛋!”他心里想,“像阿尔吉莫这样一个一等的钳工,每月才赚四十八卢布,而我每月才赚十个卢布,可是他们一天一夜就赚到那么多,这是为什么呢?一放下手中端着的菜盘子,他们就把这些钱喝掉、赌光。”

保尔认为,他们这些人跟老板一样,是另一类人,也是他的敌人,与他水火不容。“这些混蛋,他们在这里侍候别人,但是他们的老婆孩子却像富人一样在城里大摇大摆。”

有时,他们把穿着中学生制服的儿子和养得肥胖的老婆带来。“他们的钱可能比他们侍候的绅士还要多。”保尔这样想。久而久之,他对每夜在厨房的暗室里或是饭馆的仓库里所发生的事情,也不觉得惊奇了。因为他心里明白,无论哪个洗餐具的女工和女招待,要是不愿意以几个卢布的代价,将她们的身子卖给饭馆里有权势的人,那么她们绝对不可能在饭馆里长呆下去。

保尔已经窥视了生活的最深处、最底层。从那里,一阵阵腐烂的臭味儿夹杂着泥坑的潮气,正向他这个如饥似渴追求一切新鲜事物的孩子扑面而来。

阿尔吉莫想把弟弟安排到调车场去当学徒,但没能如愿,因为那里不收十五岁以下的少年。然而,保尔天天都梦想着有朝一日能摆脱饭馆这个鬼地方。是的,调车场那座熏黑了的大石头房子已经深深地吸引着他。

他常常抽空跑去看阿尔吉莫,跟着他去检查车辆,尽量帮他干一些力所能及的活。

在弗朗茜离开饭馆之后,他感到格外烦闷。

这个整天笑眯眯的、总是那么快乐的少女已经不在这里了,此时此刻,保尔更加深切地感觉到他和她的友谊是多么深厚。而现在,早上来到洗刷间,一听到这些无家可归的女工们的争吵声,他便感到有种说不出的空虚和寂寞。

在夜间休息的时候,保尔在大锅下面的火炉里添好木柴,然后蹲在敞开的炉门前面,眯起眼瞅着火——火炉的暖气让他感到很舒服。每当这时,洗刷间里只有他一个人。

不知不觉,不久前的事情又呈现在他的脑海中,他想起了弗朗茜,当时的情景又浮现在他的眼前。

那是一个星期六,正是夜间休息的时候,保尔顺着梯子到下面的厨房里去。出于好奇,在转弯处,他爬上了柴堆,想看看仓库,因为赌博的人通常都聚在那里。

他们在这里正赌得起劲,扎利瓦诺夫是庄家,其面孔兴奋得发紫。

这时,保尔忽然听见楼梯上有脚步声,回头一看,发现甫洛赫尔走了下来。保尔赶忙躲在楼梯下面,等甫洛赫尔走进厨房。楼梯下面是阴暗的,甫洛赫尔是不会看见他的。

当甫洛赫尔转弯向下走时,保尔能清清楚楚地看见他那大大的脑袋和宽阔的脊背。

接着,又传来轻声而又迅速地跑下楼梯的声音,此时保尔听见一个熟悉的嗓音: “甫洛赫尔,等一下。”

甫洛赫尔站住了,他转过身,朝楼梯上面看了看。

“什么事?”他不高兴地问道。

那个人走下楼梯,保尔认出她就是弗朗茜。

她上前拉住堂倌甫洛赫尔的袖子,用一种微弱的并掺合着啜泣的声音问道:“甫洛赫尔,中尉给你的那些钱呢?”

甫洛赫尔猛地挥了一下胳膊,于是甩开了她的手,并恶狠狠地说:“什么?钱?难道我没有给你吗?”

“不过,他给了你三百个卢布。”保尔听得出来,弗朗茜的声音里抑制着悲痛。

“什么?三百个卢布?”甫洛赫尔讥笑她说,“你想全部拿去吗?太太,一个洗盘子的女工能值这么多钱吗?我看,给你五十卢布就已经足够了。你想想,你应该知足了!那些比你干净、并且读过书的贵妇人,还拿不到这么多呢!你得到了这么多,应该谢天谢地了,只是在床上睡了一夜,就挣到五十个卢布。没有那么多的傻瓜。好了,我再给你二十来个,要是再多可不行了。你要是真识相,往后还会挣到的,我给你找主顾。”说完之后,甫洛赫尔便转身走进了厨房。

“你这个流氓,混蛋!”弗朗茜边追边骂,但没追两步她就靠住柴堆,呜呜地哭了起来。

站在楼梯下面暗处的保尔听到了这一切,他还亲眼看到弗朗茜在那儿哽咽着,还不时用头撞那柴堆。此时此刻,保尔心中的感受难以形容。但是,他并没有跑出来,而只是沉默地用力抓着那扶梯的铁栏杆,他的手在颤抖,他的脑海里涌现出一个清清楚楚、驱逐不去的想法:“弗朗茜也被这些该死的混蛋出卖了。唉!弗朗茜,弗朗茜……”

保尔对甫洛赫尔的憎恶和仇恨更加强烈了,他甚至对周围的一切都敌视起来。“哼,要是我有力气,一定会打死这个流氓!我怎么就不能像阿尔吉莫那样又高又壮又有力气呢?”

炉膛里的火忽明忽暗,小小的火苗灭了之后,又颤颤地长起来,组成一股长长的、蓝色的、旋转的火焰;这在保尔看来,好像一个人正对他吐着舌头,讥笑他、嘲弄他。

屋子里很静,只有炉子里不时发出的爆裂声和水龙头的均匀的滴水声。

凯利莫卡将最后一只擦得锃亮的平底锅放在了架子上之后,揩着手。厨房里再没有其他人了,值班的厨师和女下手们都在衣帽间里睡觉。每天夜里,厨房里能有三个小时的歇息时间。每当这时,凯利莫卡总是跑到上面与保尔一道消磨时间。这个厨房里的小学徒跟黑眼睛的小火夫已经成了好朋友。凯利莫卡上来后,发现保尔蹲在敞开的炉门前面。保尔已经看见了墙上那个熟悉的、头发蓬乱的人影了。于是,他头也不回地低声说: “坐吧,凯利莫卡。”

凯利莫卡爬上柴堆,躺在那儿,又看了看坐在那儿不动声色的保尔,笑着问道:“你在干什么?在向火炉施魔法吗?”

保尔的目光不情愿地移开火苗儿,只见他那对闪亮的大眼睛盯着凯利莫卡。凯利莫卡能看出他眼睛里藏着一种难以形容的忧郁——他这是第一次从同伴的双眼里看到这种忧郁。

过了一会儿,他问道:“保尔,今天你有点古怪……发生了什么事?”

保尔起身走到他旁边,然后坐下。

“什么事也没有,”他用一种低声回答,“我在这里很难受,凯利莫卡。”他那放在膝上的两只手紧紧地攥成了拳头。

凯利莫卡双肘支撑着身子,接着问道:“你今天究竟怎么了,为什么不高兴?”

“你说我今天怎么了?不!自从到这里干活的那一天起,我就一直不高兴。你看看这里的情景!我们像骆驼一样卖力干活,得到的回报就是谁想揍我们一顿就揍一顿,而且还不许还手。老板雇我们为他们干活,可是无论是谁,只要有力气,都可以揍我们。即便我们有分身术,也不可能把每个人都侍候周到,其中若有一个没有把他侍候好,我们就得挨揍。无论你怎样拼命地干活,尽力把每一件事做好,让别人挑不出什么毛病,但总免不了有什么小闪失,所以我们逃脱不了挨揍……”

凯利莫卡听后大吃一惊,于是打断他的话说道:“别这么大声,要是有人进来,会让人家听见的。”

保尔跳了起来:

“让他们听见好了!反正我不想在这里干了,就算到马路上扫雪也比在这里强……这儿是什么鬼地方……是坟墓,所有的人都是流氓无赖。你看他们个个都是有钱的人!他们不会把我们当人看,对姑娘们想怎么样就怎么样,要是有哪个姑娘长得漂亮点,不愿意答应他们的要求,他们就会马上把她赶走。她们能到哪儿去呢?雇来的都是无家可归、食不果腹的人啊。她们为了挣口饭吃,只好呆在这里,这里好歹也有口饭吃啊。为了不挨饿,只能听从他们的摆布!”

保尔说这些话的时候,愤愤不平,满腹仇恨。凯利莫卡害怕有人听见他们的谈话,所以急忙起身去把那通往厨房的门关上了。保尔继续宣泄着积郁在心中的一切:“你看你吧,凯利莫卡,别人打你时,你总是一声不响。你为什么不反抗呢?”

保尔在桌子旁的凳子上坐下,疲乏而无奈地用手托着下巴。凯利莫卡给炉子添了一些木柴,便也在桌边坐了下来。

“今天我们不读书了吗?”他问保尔。

“没有书读了,”保尔回答,“书亭没开门。”

“怎么,今天那里不卖书了?”凯利莫卡听了颇感奇怪。

“宪兵把那卖书的抓走了。他们还在那里搜到了一些东西。”保尔回答。

“为什么?”

“据说是因为政治。”

凯利莫卡百思不得其解地瞅了保尔一眼。

“什么叫政治?”

保尔耸了耸肩:“鬼才知道!据说,要是有人反对沙皇,这就叫政治。”

凯利莫卡吓得浑身哆嗦了一下。

“难道真有这样的人吗?”

“不知道。”保尔回答。

门开了,睡眼惺忪的戈娜莎走进了洗刷间。

“你们为什么还不睡,小家伙?趁现在火车还没有来,你们足能睡上一小时。去睡吧,保尔,我替你照看锅炉。”

使保尔感到意外的是,他很快就离开了车站饭馆,离开的原因也完全出乎他的意料。

那是正月里一个寒冷的早上,保尔本该下班回家,但是接他班的那个人没有来。他便跑到老板娘那里,说他要回家,但老板娘不答应。因此,不管他多么劳累,他还得再干一天一夜。天黑时,他已经精疲力竭了。深夜,在别人都可以休息时,他还要把几个大锅放满水并烧开,等着那班三点到达的火车。

保尔打开水龙头,发现没有水——显然水塔没有送水。他没有关上水龙头,就倒在柴堆上睡着了——他实在是太困乏了。

几分钟之后,水龙头咕嘟咕嘟地流出水来,片刻之间水便注满了水槽,接着水溢了出来,流到洗刷间的瓷砖地上。与往常一样,洗刷间夜里没有人;水越来越多,漫过地板,从门底下流进了餐厅。

一股股的水流就从那些熟睡的旅客们的包袱和提箱下流过去,但是没有人发觉。直到水流到了一个在地板上睡着的旅客身上,他突然跳了起来,大声喊叫,这时旅客们才清醒过来,纷纷慌忙抢救自己的行李物品。整个饭馆里乱成一团。

水仍是在流个不停。

正在隔壁大厅里收拾桌子的甫洛赫尔听到旅客们的叫喊声,急忙跑出来,他跳过地面的水流,冲到门边,用力把门推开。这样,原本被门阻挡住的积水便迅猛地冲进了餐厅。

叫喊声更大了。几个当班的堂倌便一齐跑到了洗刷间。甫洛赫尔径直扑向酣睡的保尔。

雨点般的拳头一个接一个打在了保尔的头上,几乎把他打懵了。

刚刚被打醒的保尔还不知道发生了什么事;他眼冒金星,浑身疼痛难忍。

遍体鳞伤的保尔好不容易才一步一步地挪到了家里。

第二天早上,脸色阴沉的阿尔吉莫皱着眉头,让保尔告诉他事情的经过。

保尔如实讲述了事情的经过。

“是谁打的你?”

“甫洛赫尔。”

“好,你躺着吧。”

阿尔吉莫披上羊皮袄,一句话也没再说就出去了。

“我想见见堂倌甫洛赫尔,可以吗?”一个陌生的工人问戈娜莎。

“他马上就来,请等一下。”戈娜莎说。

这个身材魁梧的陌生人靠在门框上。

“好,我等着。”

甫洛赫尔端着一大摞盘子,用脚踢开门,走进了洗刷间。

“他就是甫洛赫尔。”戈娜莎指着甫洛赫尔说道。

阿尔吉莫猛地跨出一步,一只铁钳似的大手紧紧地捏住那家伙的肩膀,目光逼视着他问道: “你竟敢打我弟弟保尔?”

没等甫洛赫尔把肩膀挣开,阿尔吉莫狠狠的一拳便把他打倒在地;甫洛赫尔本想爬起来,但是阿尔吉莫第二拳比第一拳更有力,把甫洛赫尔打得死死地钉在了地上,再也动弹不得。

洗餐具的女工们都吓得躲到了一边。

阿尔吉莫转身向外走去。

被打得头破血流的甫洛赫尔在地上滚来滚去。

当晚,阿尔吉莫下班后没回家。

后来,母亲四处打听,才知道他被关在宪兵队了。

六天以后,阿尔吉莫才得以回家。当时母亲已经睡着了。保尔正坐在床上,阿尔吉莫走过来,坐在他旁边,亲热地问道:“怎么样,弟弟,好点了没有?这运气还算是好的。”沉默了一会儿,他又接着说:“没什么大不了的!不要紧,你去发电厂干活吧,我给你找了份差事。再说你可以在那里多少学点本事。”

保尔双手热切而又激动地握住哥哥的一只大手。